Community engagement is key to ensure energy transitions do not perpetuate injustices

Felipe Alberto Corral Montoya is researching energy transition and social policy in Colombia, after completing a Masters in public policy with the support of an FES scholarship.

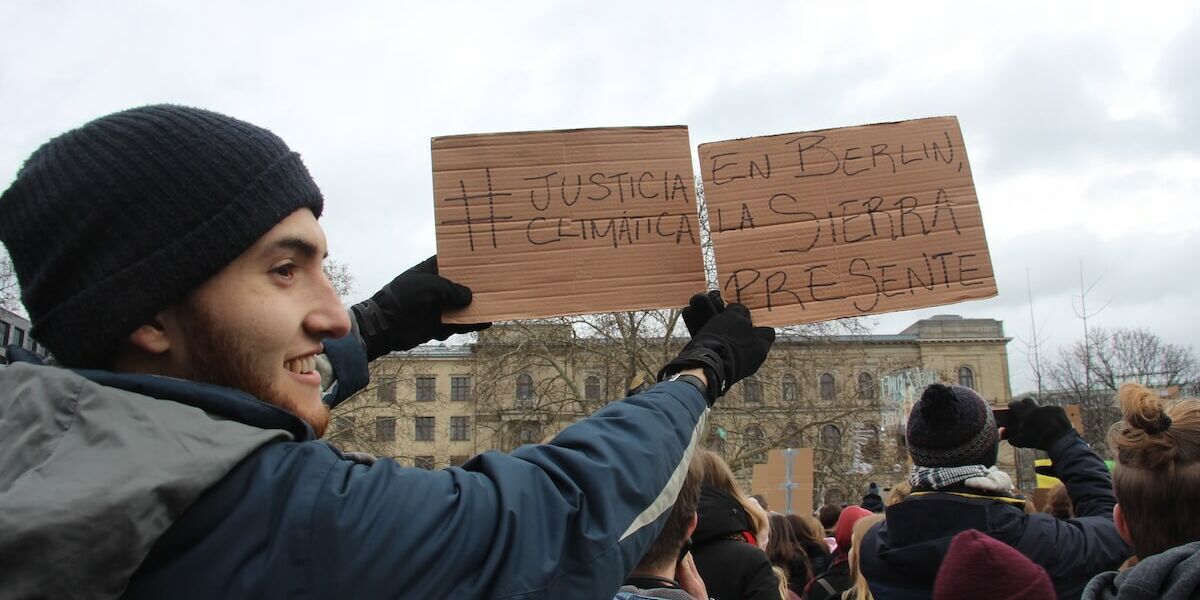

Corral Montoya, 25 and a member of the Latin Amerian diaspora in Germany, is a good example of the engagement of international youth to drive social democratic change.

He spoke to FES Connect about how a shift to renewables must be accompanied by grassroots engagement as well as State-level buy-in to ensure the welfare of local communities.

What is the focus of your work?

We are working with the community of La Sierra in Northeast Colombia to support their energy transition. Over the past 40 years, coal has come to dominate the region’s economy, providing up to 90 per cent of income in some municipalities.

We connect the community to the network of contacts, expertise, knowledge and resources that the Latin American diaspora has in Berlin. We also learn from their long experience of social, environmental and cultural struggle, and their profound attachment to the territory.

Currently we are organizing a workshop on community-led solar energy as an initial step for the community to begin orchestrating its own energy transition.

Why is grassroots engagement important for a just energy transition?

Grassroots support is key to ensure that energy transitions do not perpetuate existing injustices or create new ones. Consider La Sierra: Decades of extraction have left the region dependent on coal, but without improving its social, environmental or economic indicators. Now parts of the region are rapidly shifting towards solar and wind energy, but the large-scale, internationally owned projects appear as detached from local welfare and interests as coal extraction has been since the 1970s. Communities are not being meaningfully engaged, they have no ownership over the incoming technologies, and existing injustices are not being solved, such as chronical malnutrition or poor access to drinking water. Just because you phase out coal does not mean everything improves.

You recently defended your Masters thesis on public policy and the political economy of the coal sector. What were your conclusions?

Three things. First, if we want to learn how to phase out coal it is key to understand how it was phased in. This makes it important to consider historical accounts from a critical perspective, with regards to both economics and politics. Second, it is also key to avoid polarizing the issue, but rather to begin differentiating the roles. Once coal-sector actors are able to dissociate themselves from that unsustainable production system, the coalition sustaining the current status quo can be disrupted. Third, one way to engage in such a debate is to create just-transition dialogues and actions.

What is the role of the State in energy transition?

The State is the ultimate decider on energy and mining policies, and decides which actors it engages with. In Colombia, the State is very cosy with large corporations, especially in mining, and can maintain a certain distance from, if not disdain for, local communities. The State must shake itself free from the grip of deep-seated fossil-industry interests, and actively engage communities in shaping the transition process. This will mainly be about how to reduce energy waste in the first instance, and how to make the best social use of energy.

Energy and climate policy was not your first area of focus. What changed your mind?

I interned at the FES office In Bogotá, where I organized an event on the implications for Colombia's coal-producing regions of the phasing out of coal in Europe. I must acknowledge that if it had not been for my FES mentor Daniel Voelsen I would not have gone to Colombia. He emboldened me to take a gap year, which eventually took me to Bogotá, and then back to the Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Energy in Berlin. In Colombia, I met my current boss, who encouraged me to apply for a position as student assistant. This is how I began my academic research, which currently has me on the cusp of beginning a PhD at the Berlin Institute of Technology.

You have lived in the Americas, Asia and Europe, where many young people share concerns over inequality, violence and climate change. What is your advice on how to stay positive and engaged?

Consider becoming realistic optimists. Try to be as aware as possible about the extent of the challenges we are facing. Belittling or ignoring issues such as climate change, corruption or inequality is uninformed, irresponsible or naïve.

And alongside this awareness, try to believe that better is still possible. That we can still change things despite it all. In my case, I am inspired by the community leaders who are daily paying with their lives for their struggle for a more just, more equitable and more environmentally friendly future. If they can stay motivated and make meaningful local changes, then from my own position of shelter and privilege I can surely afford to invest in the struggle for a just change.

###

Find out how to apply for an FES scholarship by clicking this link (info in English and Spanish). If you are current or a former scholarship recipient and would like to join the FES Alumni Mentoring Programme email the FES team at mentoring(at)fes.de.

About FES Connect

Connecting people, in the spirit of social democracy, we source and share content in English from the German and international network of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.