From personal prejudice to political position: where does right-wing extremism come from?

Devaluating another person results quite comfortably in self-enhancement, which right-wing extremism uses to base a whole ideology, says social psychologist and professor for social work Beate Küpper at the University of Applied Science Niederrhein in Mönchengladbach (link).

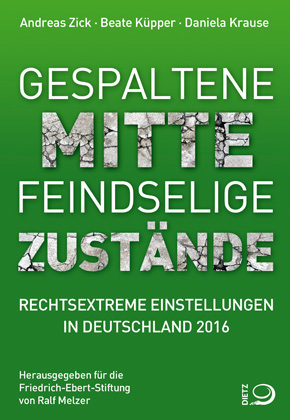

Küpper has been studying prejudices and right-wing extremism in Germany. She is co-author of the Mitte-Studie, a biannual study on extremism and prejudices in the societal mainstream published by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) as part of its continued work to fight right-wing extremism in Germany, in Europe and globally. For the purposes of the study, under the lead of the Institute of Interdisciplinary Research of Conflict and Violence of the University of Bielefeld, Küpper has monitored right-wing extremist, anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim and anti-Roma attitudes, anti-Semitism, sexism, and homophobia, as well as the devaluation of homeless, unemployed and handicapped people.

In the lead up to the 2018 World Cup, the world football governing body FIFA adopted a no-tolerance stance to racism and discrimination. We talked to Küpper to understand how perpetrators develop negative attitudes, what makes some prejudices more pervasive and destructive, the directions right-wing extremism has taken in Germany and Europe and how to fight it.

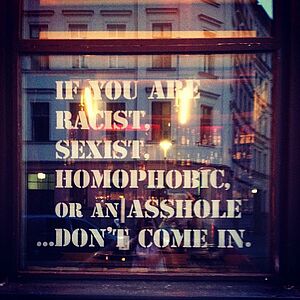

“If you are racist, sexist, homophobic or an a..hole, don’t come in!”— this inscription on a Berlin café window greets potential customers. Are people with prejudices aware how their regarding of others differently affects people? What did the findings in Denigration of the Other—your longitudinal quantitative study on prejudices—reveal about the dissemination and development of prejudices?

Most people would deny that they are racist, sexist or homophobic, but rather perceive themselves as rather tolerant. They are not aware that many of their attitudes meet the social-psychological definition of prejudices, and are likely to defend their positions with “But this is my opinion” or “This is no prejudice, this is true”.

Therefore, many people probably would not feel addressed by the inscription of the café. And they are probably not aware of how people feel who are targeted by racism daily. Or sometimes if they do care, even worse; they want to make others feel bad as a way of demonstrating their own power.

Social psychology defines prejudices as generalized attitudes towards social groups or their members as determined by dedicated markers of ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender, or sexual orientation (regardless whether the categorized persons identify with the social groups themselves or not). Prejudices can be positive or negative, but the negative ones have much harsher consequences for the targeted persons. Gordon Allport, the founder of modern research on prejudice, defines prejudice shortly as thinking negatively about a person without knowing them.

Prejudices are quite resistant to facts as there is almost always a person that meets the stereotypes, and because members of social groups who do not meet the stereotypes are not really taken into consideration. Take as example a common phrase: “Ok, Ahmed is a nice and trustful guy, but all the other Muslims …”. Prejudice can be expressed in a blatant way, fiery and direct, but often also in a subtle way as the social norm not to be racist supresses blatant forms of prejudice. One way to express prejudice in a subtler way is to overstress cultural differences e.g. between Muslims and non-Muslims. Another way is to maintain that everybody is treated in the same way while denying existing inequalities, or to address a group with stereotypes that are seemingly positive (e.g. women are much more emotional intelligent, helpful, child-loving and have a natural inclination for housework) but that are used to legitimate inequalities.

Mexico fans present in Moscow are under investigation for alleged homophobic chants directed at Germany’s goalkeeper Manuel Neuer during the 1-0 World Cup win over Germany on 17 June. Neuer is known to have encouraged gay football players to come out and not fear reactions by fans. Why are prejudices against sexual orientation, gender or skin colour so pervasive, and what makes these prejudices so destructive?

Prejudices towards several groups are deeply embedded in our cultural heritage and narratives. That applies particularly to anti-Semitism and sexism.

To be targeted by prejudices can make things really difficult. It is very frustrating, sad and unfair, and can result in less happiness, more stress, headaches, heart problems etc. Prejudice also overshadow the perceptions, evaluations and decisions of the perpetrators, for example when searching for reasons of negative behaviour: Maybe the German team was playing so badly and lost against Mexico in the first game of the World Cup because there are too many gay players on the field, they are not men enough. Maybe the thoughts of Russian hooligans reflect a fear of their own feelings towards other men, as per some psychoanalytical thought.

How does a prejudice evolve, from nominal judgment to grounds for classification and eventually fuel for extremist tendencies? In other words, how do prejudices become a resource for right-wing extremists and other negative social behaviours?

Gordon Allport described the escalation of prejudice—and I would agree—from simply ignorance, e.g. with respect to non-heterosexual love, important religious days or rules of non-dominant religions. It starts then with some nasty little jokes, continues with verbal attacks and social distance (not inviting a person from an ethnic minority or an LGBT person to your party, in your work team, as neighbour in your house), and ends up in discrimination or finally even violence or genocide. Prejudice serves then to legitimize myths that in turn justify and explain privileges and discrimination.

Devaluating the others results quite comfortably in self-enhancement. Right-wing extremism uses that self-enhancement as a basis for a whole ideology and that´s where prejudices and extremism meet.

It all starts with categorizing people into “us” and “them” along the lines of markers of ethnicity, nationality, gender etc., continues with attributing stereotypes to both groups and usually ending up with evaluating one’s own ingroup (the group a person identifies with) more positively, and the outgroup more negatively. We all think that “we” are better than “them” and therefore, that we are personally better, deserve more of the attractive goods (space, work, water, women). Devaluating the others results quite comfortably in self-enhancement. Right-wing extremism uses that self-enhancement as a basis for a whole ideology and that´s where prejudices and extremism meet.

Right-wing extremism proposes and believes in a homogenous Volk, or “people”, naturally related by blood and territory, that is genuinely different from and better than others. Anti-immigrant, anti-Semitic, racist and also sexist and homophobic prejudices therefore are a consistent part of right-wing extremism. While the Volk is conceptualized as homogenous, it is supposed also to have one single Volkswille or “people’s intention” that can best and most directly be represented by one leader, who feels what the people want. Right-wing extremism therefore lives off myths and also has sort of a spiritual character. This is what makes it so attractive for those who feel under-recognized, that they do not have as much power as they think they deserve.

You have stated elsewhere that Germany is deeply racist and anti-Semitic. In what way? How have right-wing extremist orientations changed over the past decade in the country?

For many years we have been monitoring right-wing extremist attitudes and also several types of prejudices in the so called “FES-Mitte-Studie” [“Mitte” means the societal mainstream in social, political and economic aspects] under the lead of Andreas Zick and in the preceding study on group-focused enmity directed by Wilhelm Heitmeyer, both from the Institute of Interdisciplinary Research of Conflict and Violence of the University of Bielefeld.

In these representative opinion polls we have observed overall a slow decrease of prejudice towards several social groups in the last decade—so even Germany has become more tolerant (compared to other Western European countries Germany was comparably less tolerant in general). In particular the devaluation of LGBT people and women has dropped and prejudice was, if expressed, rather subtle. However, in recent times even blatant racism has been coming back.

Forty per cent of the respondents agreed that “Germany society is undermined by Islam”, a conspiracy spread by the new right.

In our last survey in 2016 for example 13 per cent of the respondents agreed that “The white race is deservedly the leading race in the world.” Old-fashioned but also new right-wing extremism is on the rise again: 40 per cent of the respondents agreed that “Germany society is undermined by Islam”, a conspiracy spread by the new right.

While the silent majority of the German population rejects right-wing-extremist and racist attitudes and expressed their strong commitment towards democracy and diversity in the surveys, a contrasting minority is becoming louder, as well as more aggressive and violent. This minority has got and still gets too much attention and understanding by politics and the media. As a consequence, the new right was able to infiltrate successfully the discourse and now even politics.

What turn do you expect for right-wing extremism and right-wing populism to take in Germany? How is this a Europe-wide and a global challenge and what can we do collectively to fight it?

Compared to other European and non-European countries Germany is rather late in the newly widespread rise of right-wing extremism and populism. There have been right-wing extremist attitudes, groups and parties continuously since the Nazi era, but now it is becoming loud again. The national security authority reports a dramatic increase of violent attacks against refugee camps as well as Jewish graveyards and synagogues, motivated by political right-wing attitudes. More often than before, perpetrators are citizens previously not connected within the organized right-wing scene. The demonstrations by PEGIDA and the anti-Islam, anti-immigrant and anti-refugee discourse in parts of the politics and media has given the grounds for those violent attacks.

Remember the horror of what can happen if prejudice and right-wing extremism wins and of the importance retaining a strong democratic compass.

It is important not to give up on the fight for more diversity and equality. We must not tap into the easy trap of prejudice either blatant or subtle, be careful of categorization, long-lasting stereotypes and myths about whole groups of people. We need to speak out loudly against everyday racism, but be friendly without blaming people who are not aware of their prejudices. Be honest towards your own prejudices and rethink them. Do not give too much attention to right-wing-populists, you can hardly fight against them with facts. Instead, follow your own democratic goals, pay attention to democratic engagement, look out for and point to similarities instead of differences with “strangers”, remind yourself to exercise empathy, perspective taking and big-heartedness, which actually is another way to feel better about yourself. Get involved in networks, together with other democratic partners, e.g. from churches, the economy, and foundations. Share ideas and resources, e.g. write to your local parliamentarian and express your position (especially of those parties giving in to or even shamelessly using prejudice). Complain to the media when they serve prejudice and give forum to right-wing populists. Occupy social media.

Remember the horror of what can happen if prejudice and right-wing extremism wins and of the importance retaining a strong democratic compass.

###

For more information on the Mitte-Studie and the work by FES against right-wing extremism contact Franziska Schroeter, responsible for the dedicated project at FES Forum Berlin (link in German).

About FES Connect

Connecting people, in the spirit of social democracy, we source and share content in English from the German and international network of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.