Bridging Social Capital – A new attempt on SDG 16 Peace in Afghanistan and Pakistan

Once the reason or reasons behind a conflict is understood, there should then follow an understanding of the rational conflict between divergent interests, that can then in turn hopefully be resolved through legal agreements.

Following this idea, Germany hosted one of the most advanced attempts ever to achieve peace in Afghanistan. In line with the Afghan tradition of the Loya Dschirga, or Council of Elders, the Bonn process invited leaders and representatives of tribes of the 34 Afghan provinces to Bonn on 27 November 2001, just two months after the 9/11 attacks in the United States.

In October 2001, British and US forces invaded in Afghanistan to support a regime change. After a further 16 years and the subsequent involvement of many other nations’ armed forces, including Germany, lasting peace and reconciliation is still not established in Afghanistan.

The concepts of governance and rule of law portray conflicts as being a simply question of compliance with rules and regulations. Paradoxically, this perspective brings up an entire obstacle for peace: According to the UN Charta of 1945, war is only permitted in the cases of either self-defence or of a unanimous decision of the UN Security Council. Neither fit the wars “on terror” in Afghanistan and Pakistan. The Helsinki Act of 1975, which helped to end the Cold War, contained the principles of sovereignty, judicial equality and territorial integrity.

In foreign aid, the legal and security perspective—represented in Afghanistan by ISAF—competes with the development perspective, which identifies poverty as a major cause for internal violent conflicts.

As a result, the Federal Republic of Germany is addressing the case of Afghanistan and Pakistan—both countries are blaming each other for enduring clashes across the border—on the level of three governmental agencies: The Ministry for Development addresses issues such as nutrition, health and education. The Foreign Office tries to enhance governance, civil society and legal institutions. The Defence Ministry tries to improve the security—including to allow the US government to launch drone attacks in Pakistan from German Air bases.

Stepchild SDG 16 Peace?

Among the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDG) on which in 2014 all 193 United Nations members agreed, Peace (SDG 16) has been sidelined by major donors and organizations such as the OECD, the World Bank and the EU. There is no discussion about this. It may be suspected that addressing SDG 16 first will evoke controversial positions for the major areas of conflict. On the other hand, SDG 16 is a good occasion to review the current perspective on peace in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

As shown by the recent results from the UN SDG Partnership project, the World Social Capital Monitor, the Social Capital shared in both countries resemble each other closely.

Key asset hospitality: Similar social capital profiles of Afghanistan and Pakistan

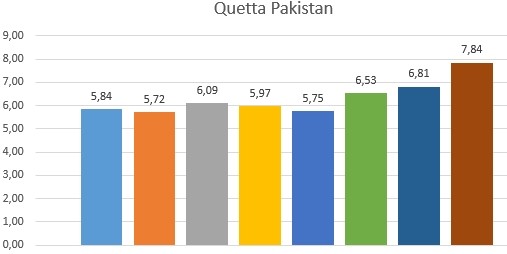

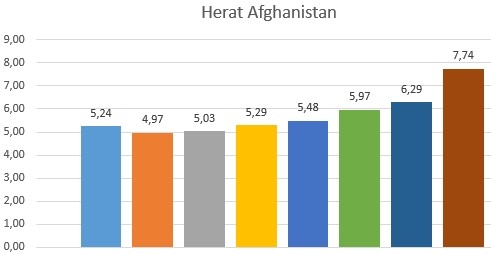

In the Pakistani town of Quetta, a Pashto town with leading Quran Schools, the social goods show the same pattern as in Herat (see images). Hospitality (brown) is the major social asset in these two regions entirely differing by language, tribe and religion. Trust (orange) is low in both towns.

Legend (columns from left to right): Social Climate, Trust, Acceptance of austerity measures, Acceptance of taxes, Acceptance to invest in cooperatives and SME, Helpfulness, Friendliness, Hospitality.

When groups share the same values and perceptions, this is called bridging Social Capital. Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz, contributor to the issue within the World Bank in 1998, called Social Capital a tacit knowledge. So why not addressing frozen conflicts by identifying bridging aspects between the conflicting parties? The towns of Quetta and Herat could become sister towns, such as many German and French towns did after World War II. Enduring peace cannot be brought about by legal commitments alone. If yes, the UN Charta would have been respected as well by the United States and Russia. If yes, the Helsinki Act from 1975 would still be valid in Europe.

Bridging social goods such as trust, solidarity, helpfulness and hospitality are the source of any peace and reconciliation.

Seeking out and identifying the rational argument behind can have the effect of fanning the flames of that conflict. Bridging social goods such as trust, solidarity, helpfulness and hospitality are the source of any peace and reconciliation. So, considering them within the SDG 16 process can be a new attempt to overcome two biases currently present in addressing conflicts:

- Attributing conflicts to a lack of governance and rule of law gives undue importance to regime change;

- Attributing conflicts to poverty and missing education gives undue importance to economic interventions from abroad, e.g. in foreign investment, agriculture and schooling.

Nevertheless, the countries fomenting wars by delivering weapons and starting interventions since decades are mostly affluent countries with advanced legal institutions. It’s the rich that bring war to the poor. Understanding their motivations didn’t help the United Nations to prevent them from violating the sovereignty of others. In the end, it is like couples’ therapy: instead of repeating all the reasons for the separation the mediator focusses on the common issues of children and family budgets. So why should outdated and inefficient ways to interpreting conflicts by religion, poverty and ethnicity continue to be the knowledge base of foreign funding and interventions?

New types of peaceful attempts to overcoming frozen conflicts such as considering culture and social capital, offering open participation in surveys and democratic processes, and allowing conflicting parties to make their points are crucial for SDG 16.

To appreciate the social capital of conflicting parties in frozen conflicts such as in Palestine, North Korea, Ukraine and Crimea, Eritrea, Syria, Iraq, West Africa, Yemen, Afghanistan and Pakistan will meet the motto of the SDG which is “leave no one behind”. Instead of providing unilateral standards we may enhance what we expect in our culture as well: to have our own values and social goods considered and respected. ###

As student of the Nobel Prize winner and researcher on public property Elinor Ostrom (died 2012), Alexander Dill founded the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics in 2010. The Institute is specialised on the measurement of social capital. Since 2016, Alexander heads the UN-Partnership Project "World Social Capital Monitor" and in this function, he assesses social goods worldwide.

The views expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

Sources used:

UN-Website Social Capital Monitor