A last chance for Italy's flawed democracy?

On 15 September, we celebrated the International Day of Democracy. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic this celebration occurred in a year in which many democracies had to take decisions that drastically limited rights and freedoms and in which authoritarian regimes and those who would like to become authoritarian took advantage of the situation to increase their power.

It will take time, perhaps years, to assess the full impact the pandemic will have had on the democracies of the world. And the magnitude of the impact on democratic functions will depend on how long the health crisis will last, how it will damage economies and society and how democracies compared to autocracies will have been able to contain the negative health, economic and social consequences.

Even before the pandemic, democracy was already experiencing one of its most complicated periods. Many indices, for instance the Freedom House, Democracy Index, V-Dem and SGI, had grasped this trend, which in recent years in particular has led to talks about worldwide democratic recession.

Italy too has seen several setbacks. Some aspects such as electoral processes, civil rights and political freedom, pluralism and the rule of law are satisfactory. However, numerous other factors make Italy a flawed democracy: abstention rates increase at every election, the delay in public administration and the inefficiency of the functioning of governments have even become permanent features of the political system. Political culture remains significantly underdeveloped, and, last but not least, media freedom is only partial.

Moreover, after a longstanding economic crisis, the country appears to be torn apart by social and economic tensions, by deeper inequalities between rich and poor and between north and south, and by a growing distrust of national and international institutions. All this is leading to a polarization between libertarian, cosmopolitan positions and more traditionalist orientations on issues such as immigration, crime, minority rights and the environment.

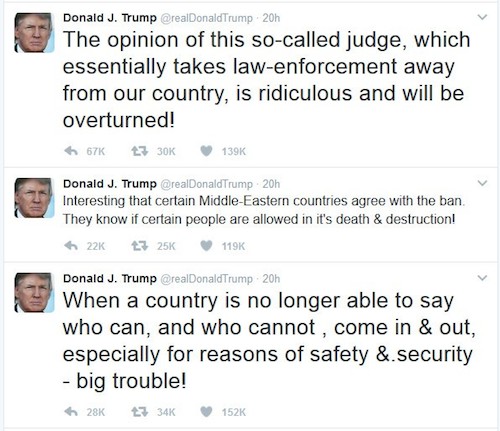

Populism in its many forms including populist right-ring parties like Lega and Fratelli d’Italia (Italy’s Brothers) have taken advantage of this cleavage and, with the illusion of simple answers to the various problems, they attract more and more sections of the population that have now lost hope and interest in politics and the established mainstream parties. And democracy pays the price.

In such a worrying context, it seems essential for Italy to encourage deep reflection at all levels on the political, economic and social assumptions of democracy. It is crucial to overcome the procedural dimension of democracy and to refocus on its substantive conception, intended as equality, access and universalisation of rights as well as distribution of resources and opportunities. The road to a substantive version of this dimension of democracy in Italy still seems long and the post-COVID period will probably lead to an increase in social and economic tensions in a divided and unequal country. However, the exceptional reconstruction measures such as the recovery plan for the EU and its member states (Next Generation EU – NGEU) and the funds foreseen for Italy (some 209 billion Euros from grants and loans) are a great opportunity for the Mediterranean country, and maybe the last chance to reduce inequalities, fight against populism and eventually strengthen its democracy in all its forms.

Whether the current and future Italian governments and institutions will succeed in reducing inequalities, in strengthening the rights of each individual, in improving the efficiency of the public apparatus, in reducing the feeling of anti-politics, and in encouraging Italians to participate more actively in public life, remains an open question for now. It is a complex, forward-looking and long-term task that requires many measures and investments in education, digitization and empowerment of each individual in Italian society. It would in turn enable social and political inclusion – pillars of democracy – and would counter populism more vigorously.

If the implementation of the NGEU fails, not only the economy, but Italian democracy would suffer greatly, and the path forward would be extremely complicated. Given the democratic setbacks, a massive and growing populist tendency in the country and a possible crisis of social stability, a progressive move towards an authoritarian course cannot be excluded.

Whether one wants to call our time the "era of inequality", in the words of Francis Fukuyama, or the "era of populism" (Ivan Krastev) is of little importance, as it is a rather academic discourse. But it is clear that inequality, democracy, and populism go hand in hand. One false step of the first one could further jeopardize the second one and enhance and spread the last one.

About the author

Luca Argenta holds a Master’s degree in European Studies. He is currently a PhD student in Political Science at the “Europa-Universität Flensburg” and works as research fellow at the FES Italy Office. He regularly writes about European affairs, German and Italian politics. His main research interests include European integration, European governance, democracy and populism.