South Africa's dilemma in the Belt and Road Initiative: Losing Africa for China?

On 16th of February 2018, South Africans eagerly watched their new President Cyril Ramaphosa deliver the State of the Nation address in a drought-stricken Cape Town. The speech left foreign policy experts underwhelmed as to the strategic vision of the country.

South Africa is part of the international trend that has seen several powerful states turn inwards in response to an allegedly unjust global economic system. Within this trend Ramaphosa in his speech effectively reduced foreign policy to a type of economic diplomacy (link in English) that would assist the country in its pursuit of economic transformation, capable of addressing the country’s triple challenge of poverty, inequality and unemployment.

"The country [South Africa] added legitimacy to the Global South grouping not just by its own inclusion, but also by its representation of wider African interests in an unjust and skewed global economy."

Experts comparing the country with the heyday of former President Nelson Mandela, see this as another instance of South Africa abandoning the human rights stance that earned it acclaim in its relations with the Global North, and moving towards a more self-interested position. More specifically, the country is called out for gravitating towards China through the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with Beijing, its trade relationship that has seen China become South Africa's largest trading partner for eight consecutive years and its burgeoning relationship in BRICS, the association of emerging national economies where South Africa joins Brazil, Russia, India and China.

But seemingly at odds with this alliance of mutual benefits and win-win rhetoric, Beijing’s most ambitious foreign policy agenda, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is delivering a tough blow to South Africa's international standing, especially as China forges its path alone through the rest of Africa.

South Africa’s Africa focus

Notwithstanding its history and stance regarding human rights, at the heart of South Africa’s foreign policy (link in English) is a deep-set recognition of how closely the country’s own trajectory is tied to that of the African continent. In fact, South Africa’s entrance in 2010 to the BRIC group of countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China) relied on lobbying (link in English) that the country added legitimacy to the Global South grouping not just by its own inclusion, but also by its representation of wider African interests in an unjust and skewed global economy.

South Africa's relative economic strength and pan-African footprint allowed it to adopt the role of gateway (link in English) to the African continent. South African foreign policy actors promote the country’s self-appointed role as gatekeeper to the continent was its raison d’étre for its prominent international standing. This self-perception by South Africa is propped up by international business ventures and grand diplomatic gestures such as the launch of the China-South Africa High Level People-to-People Exchange Mechanism in 2017 (link in English). But the onset of the BRI is exposing fissures in the BRICS grouping (link in English) that even South Africa cannot overlook in its alliance with China.

"Support in Africa [for the BRI] is not unanimous. Interest is dependent upon proximity to the BRI and the availability of alternative options for economic growth."

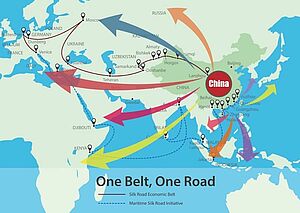

At the centre of the BRI are two physical routes linking Asia, Africa and Europe. While cynics scrapped the idea as fantasy, China is pulling followers, engaging countries as far afield as Latin America and the Caribbean (link in English). Certainly, there are challengers to this plan especially from within BRICS, where India and Russia are the most prominent obstacles for China. On the other hand, many enjoy China’s perceived inclusive approach (link in English), a strategic move from China, which needs to pull together a whopping 4 trillion US dollars in future funding (link in English).

Africans more readily embraced the plan and its expected ripple effects, perceived as a necessary step for economic growth on the continent. Still, support in Africa is not unanimous. Interest is dependent upon proximity to the BRI and the availability of alternative options for economic growth.

BRI supporter and China-Africa expert Yu-Shan Wu at the South African Institute for International Affairs, argues that the BRI is favourable for Africa because it is in line with the development objectives of the Agenda 2063 of the African Union (AU). Other critics, such as Ronak Gopaldas of the Institute for Security Studies, suggest that a grim fate awaits African states who risk falling for China’s debt-trap-diplomacy (link in English).

BRICS is a prime vehicle for South African ambitions

South Africa’s own foreign policy aspirations are not only geared towards African prosperity. Rather, it is ambitiously aiming to re-write global financial rules towards more equitable global governance institutions. BRICS, the grouping tied by a common normative underpinning (link in English), is the prime vehicle for South Africa’s foreign policy execution. South African Sherpa for G20 and BRICS Dr Anil Sooklal maintains that despite being the smallest emerging market in the forum, South Africa is an equal partner (link in English).

Others have observed that this influence translates to a voice at the BRICS table for the African continent. "With South Africa as a permanent member, Africa is not left out of major decisions made by other developing nations," writes Singapore-based management consultant Richard Li (link in English). "Africa instead, has the opportunity to contribute to the decision-making process and Africa stands to reap the benefits from the economic cooperation among the BRICS nations."

South Africa also stepped up to ensure access to the bloc by African leaders, inviting representatives to the coastal South African city, Durban, during the fifth BRICS Summit in 2013. This extension did not raise eyebrows as it is common practice for neighbours of the host country to be invited to the summits. But the dynamic changed after China unveiled the BRI in 2014, and started to pursue its continental agenda without going through South Africa.

"During the Chair of the AU Commission, China and the AU signed memoranda of understanding (MOUs) for the BRI that included cross-continental infrastructure development. It is unclear how these AU MOUs affect, overlap and intersect with national interests, national expressions of authority and national MOUs with China."

First, Beijing made clear its growing affinity for other African states connected to the BRI, notably Kenya, Tanzania, Djibouti, Ethiopia and other emerging hubs in East Africa.

Second, China’s insistence on including BRI in different forums, especially BRICS and the Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) where there is no coherent African response, means there is no measure to control China’s influence in continent-wide development. Typifying the lack of synergy within Africa is that during the Chair of the AU Commission (link in English), China and the AU signed memoranda of understanding (MOUs) for the BRI that included cross-continental infrastructure development. It is unclear how these AU MOUs affect, overlap and intersect with national interests, national expressions of authority and national MOUs with China.

Third, China seems to be outgrowing the parameters of the BRICS and is exploring new formations. China seems to be exploring two options, either by expanding BRICS to a BRICS Plus Approach where the likes of Egypt and Kenya are stakeholders—which compete with South Africa’s standing within BRICS. Alternatively, China will focus an increasing amount of energy on BRI and less on the aims of BRICS or on its loyalty to the commonly articulated world vision with South Africa.

South Africa's international standing without its Africa clout

With other African states in favour with China today, South African-based experts (link in English) no longer speak of South Africa as a gateway to the continent, nor do experts acknowledge that there is any contest for the spot by other African nations. Instead, the convergence is that several points of access are already present in Kenya, Nigeria etc.

Tales are slowly coming to the fore of China’s debt-trap diplomacy or the consequences for those who dare to threaten the One China Policy which South Africa is now experiencing

As South Africa struggles to find a new role on a stronger continental plane, China is poised for partnership, armed with its improved set of public relations. As for what this means for African states, tales are slowly coming to the fore of China’s debt-trap diplomacy or the consequences for those who dare to threaten the One China Policy (link in English) which South Africa is now experiencing.

Ultimately, as China primes certain African partners, it is in China’s control to decide which African states rise with it. As such, without the guiding hand of pan-African institutions, Africans are encouraged to compete against each other for economic relations with China and essentially, influence on the continent. This reality opposes the widespread African consensus that the best strategy for a prosperous Africa is pursuing external relationships as a unified Africa.

"Disarmed of its identity, we must ask what will happen to the wider African continent when South Africa is unable to perform its role, depicted at best as protector of the African continent or, more cynically, as self-proclaimed gatekeeper."

South Africa tried to corroborate a proactive African narrative (link in English) to relations with China through FOCAC under its chairmanship. Though it is to be reviewed whether South Africa had any success, it is promising news in 2018 that AU adopted institutional reforms (link in English) to ensure coherent external relationships with the continent in future. However, the implementation of the BRI continues and time is against Africa.

In the end for South Africa, without the Mandela glow to enhance its international standing nor its claim as a gateway to Africa, there is little left of its foreign-policy identity. Disarmed of its identity, we must ask what will happen to the wider African continent when South Africa is unable to perform its role, depicted at best as protector of the African continent or, more cynically, as self-proclaimed gatekeeper. It is, worryingly, South Africa’s loyalty to China within BRICS, South Africa’s one visionary foreign policy project, that ironically delivers this final blow to its international standing in what may be a calculated game to direct the continent’s future.

In the midst of South Africa’s preparation for the 10th BRICS Summit this year, the onus falls on South African civil society to push President Ramaphosa into ruffling some feathers in BRICS. South Africa can no longer afford to meander without strong foreign policy positioning—this may require re-evaluating its approach to some friendships. ###

Tamara Naidoo is programme manager for international affairs at Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung South Africa. In 2017, FES South Africa worked with partners on a report with recommendations for a pan-African policy and strategy to guide Africa’s engagement with China. For more information about the current work focus and activities visit the country office website.