Will Nairobi’s ambitious renewal project secure residents' social rights?

Nairobi is popularly referred to as the ‘The Green City in the Sun’. It boasts a National Park where you may see the Big Five on its outskirts and is the East Africa’s commercial hub. Amid this beauty is an acute shortage for affordable housing.

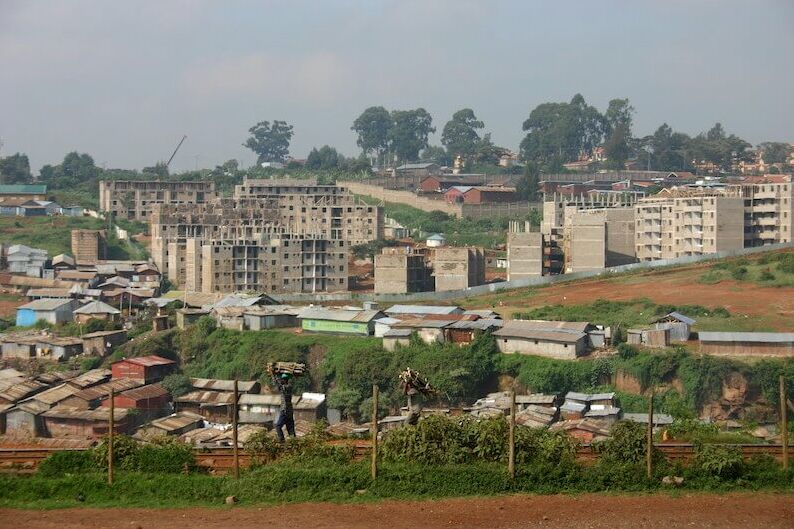

With the suburbs included, Nairobi is Africa's 14th largest city with 6.54 million people according to World Population Review. Most of them live in informal settlements and old city council estates where provision of sewerage, water supply and security is unreliable. Their social rights have yet to be secured. There was great excitement in November 2016 when former Nairobi Governor Evans Kidero launched the Urban Renewal Programme, promising the urban poor new and modern housing to replace their old dilapidated dwellings.

The programme is to be implemented by the Nairobi City County as mandated by the Urban Areas and Cities Act 2011. It aims to re-plan and redevelop many of the city’s old estates and replace them with modern high-rises. It is also one of the flagship projects of Kenya’s Vision 2030, which envisions the project as a sustainable mini-city. It will affect a total of seven estates housing over a million lower-middle class residents, and will cost over 300 billion shillings (2.9 billion US dollars). The money will come largely from private investors while the City County provides the land.

The targeted estates are among the oldest in Nairobi, with some built by the British colonial government, before independence as part of their city’s first Master Plan devised in 1948 to guide development for 25 years. The post-independence governments didn’t control unplanned development.

Therefore, they are now in disrepair due to lack of proper management and pressure from massive rural-to-urban migration. Overcrowding, blocked sewers and lack of clean water afflict these estates daily. The relatively low rents have drawn the less well-off and some criminal elements, and crime is widespread.

"It was like different city–lawless, crime ridden and full of diseases I was pretty sure I hadn't been immunized for," Alex Stonehill of The Slum Rising project says of his arrival in Kibera on arrival from the US. Ms Angela Atieno, a hairdresser and resident of Kibera’s upgraded slum complains, "My family of four shares a house with two families with four members each. We have many problems, especially when it comes to sharing the kitchen."

But the residents have put on a brave face, unaware of their social rights, as they had nowhere else to go.

The new project promises to ensure their social rights are protected. The governor has insisted that the respect of these rights will be improved. He promised that they will be given a chance to choose where to move and also own the houses once complete.

“No tenant should be afraid of being thrown out. They will be given cash bails to rent houses somewhere else while the project is ongoing,” said then County Director of Communications Walter Mongare. The relocation is to be sensitively carried out and through consensus between the residents, developers and county.

The redevelopment approach did not address the fundamental economic empowerment of the community that would be necessary to sustain these better livelihoods, claim residents.

Yet there are concerns that these may be empty promises and that social rights of the residents might not be guaranteed. This is due to failures experienced in previous similar projects. One of the notable ones was the Kibera slum upgrading project. It is estimated that once the new Kibera high-rises were completed, almost half of the 600 families who were supposed to benefit from the programme were unable to move in. This is because the government demanded a deposit equivalent to 1,300 US dollars before residents could take possession of their new home, which many could not afford.

Many years later, the Kibera high-rises are dilapidated, sewers blocked, without running water, the same issues that were said to be a thing of the past when the project started. "The residents themselves are required to form management committees to run the place," claims Mr Charles Sikuku, Director of the Kenya Slum Upgrading Programme (Kensup). "If any problems arise, it is their responsibility to resolve them through the committees."

A study on another project in Majengo in the east part of the city revealed that residents cited improved living standards. All the same they claimed that the redevelopment approach did not address the fundamental economic empowerment of the community that would be necessary to sustain these better livelihoods. They are now grappling with unaffordable rents and mortgages.

The new project promises that those who were tenants will continue to pay rent to the City County and other houses will be available for mortgage at prices lower than current market prices. As we speak the project has not yet started due to delayed title deed processing and lack of compensation for tenants.

A similar project by then president Mwai Kibaki in 2012 failed to upgrade the living environment of the area through improvement of access to basic services such as shelter, water and sanitation, education, health, security, employment and income generation opportunities. The promises of a new project continue to feed hope among residents, but the question lingers in the minds of many whether their social rights will be protected. ###

Titus Kaloki is Programme Coordinator at Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Kenya. The views expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.