A guilty silence

The subject of immigration receives scant attention within the already precarious intergovernmental dialogue in Latin America and the Caribbean, despite the fact that many countries in the region expel populations or serve as clandestine transit routes for migrants fleeing violence, or seeking better opportunities in the United States, a country with which there is no agreement on the issue.

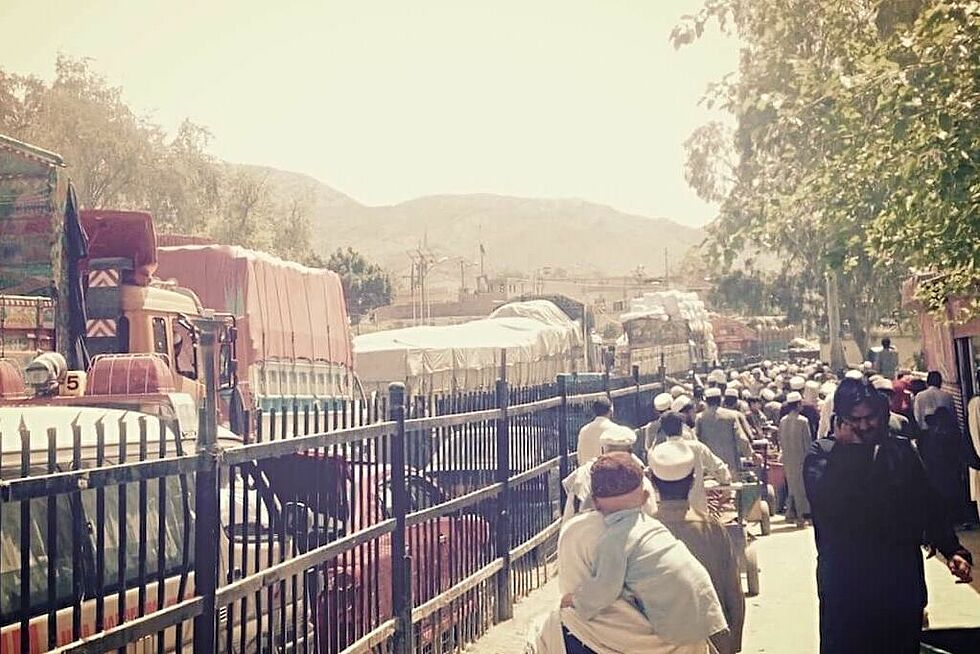

The American Dream attracts people who travel without visas from Asia (especially India, Nepal, Bangladesh, China and Pakistan), Africa (primarily Senegal, Ghana, Congo, Somalia), the Middle East (Syria), Latin America and the Caribbean (in particular Central America, Haiti and Cuba).

Cuban emigration has been constant due to the location of the island and the Cuban Adjustment Act, which since 1966 has granted them residency, work permits, social support and family reunification. In 1994, before the huge increase in dinghies making their way through the Straits of Florida, Washington decided that migrants intercepted at sea would be returned to Cuba, and only those who succeeded in stepping onto US soil would receive the benefits. Fearing that normalizing of relations between the US and the island would lead to the restriction or abolition of this law, and that Raúl Castro would take the opportunity to lift restrictions on travel and the sale of housing, Cuban migration has intensified and changed route.

Once Ecuador abolished visas in 2008, Cubans began to arrive there by plane, along with other migrants from outside the continent seeking to clandestinely cross this and seven other countries (Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico) to reach the United States. As of 2016, Ecuador has accepted the request from its neighbours to reintroduce the visa. The number of migrants arriving in Brazil and who continue via the Amazon through Guyana, or directly through Colombia, has increased. Cubans also migrate from Venezuela where they have arrived on exchange programmes and whence they defect.

For Central American countries expelling populations, the flow of more than 30,000 Cubans in the last two years has become too much to handle. Each country tries to offload the problem onto its neighbour. On 15 November 2015, Nicaragua closed its border with Costa Rica to prevent the entry of 8,000 Cubans. In mid-December, Costa Rica closed its border with Panama and prevented the entry of more than 1,000 Cubans, and to facilitate the departure of those who were already there, laid on an air shuttle with El Salvador, Guatemala and Mexico. In May 2016, Panama closed its border with Colombia and launched “Operation Shield” to “shield” the country against drug trafficking, and sent Cubans who could afford transportation to Mexico; the others were returned to their Colombian entry point, where people who have already begun their 8,000 km journey arrive. The problem has become concentrated in this area.

The Colombian Foreign Minister considered the Panama measure appropriate because it could combat illegality, help Colombia from becoming a country of illegal trafficking and maintain the transit of Colombians who have resolved their migratory status. Along with his Ecuadorian counterpart, he announced an agreement on deportation, a control on irregular border crossings and coordination between the migration authorities of both countries, and Panama.

A month after these measures have been put in place, the problem, far from being solved, has been exacerbated for migrants and for small Colombian towns, where incomers outnumber the residents living there. Tired and financially ruined migrants, pregnant women and small, sick or injured children face food, water and housing shortages, overcrowding and health risks. Villages beset by hardships are seeing their already precarious living conditions dwindle. Local authorities say this unsustainable situation could lead to a humanitarian or public order crisis. Colombian Migration, Naval and other national bodies believe that these people should be granted safe passage to leave the country and return to the most recent border that they crossed.

Some try to reach Panama by night, crossing the Gulf of Urabá, despite the danger posed by waves, to reach completely unsafe and illegal vessels. Others try to travel through the dense Darien jungle, shared by Colombia and Panama. Many are abandoned at sea or in the jungle. For $2,000 and in exchange for carrying between 5 and 20 kilos of cocaine on their backs, mafias and smugglers try to pass migrants through the jungle; the heavier the drug loads, the greater the funds they can secure to cross Central America and then pay the $5,000 demanded by Mexican ‘coyotes’ for passage to the United States.

The countries of origin, transit or reception limit their actions to detaining, criminalizing and deporting migrants, without giving any greater protection to people who are risking their lives and are victims of all kinds of dangers. Human trafficking networks and corrupt officials rob, abuse and even murder them. Migrants spend several times more than a flight would cost them from their country to the United States, but as they do not receive visas they must pay more than $10,000 to human traffickers and in bribes to civilian, police and military authorities.

The Community of Latin American and Caribbean States ignores the issue. The same is true at summits of the Americas. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights can do little, threatened as it is because the States do not provide funds for its operation. Meanwhile, Trump stirs up racism and calls for his country to seal its doors.

First published in Spanish, by Nueva Sociedad, June 2016.

About FES Connect

Connecting people, in the spirit of social democracy, we source and share content in English from the German and international network of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.